At the time of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, I was a teenager still forming my beliefs about a world that already seemed headed towards the abyss. That conflict, along with the elite deceptions, failures, and crimes that accompanied it, has shaped my worldview to some degree up til the present day. It was also the episode that first radicalized me politically. As a young person I attended protests, wrote articles, promoted boycotts, and did whatever else I could to try and stop a ruinous conflict that seemed certain to destroy the lives of millions.

Like most antiwar young people, then and now, I was attracted to the aesthetics of left-wing dissidence, as well as the tantalizing promise that by addressing one issue, a whole range of other injustices, from wealth inequality, to racism, to ecological destruction, could also be addressed. Opposition to the Iraq War became a meeting point for movements seeking to challenge the U.S.-led global economic order, raise awareness about climate change, and tackle issues of racial and gender inequality. Protests against the invasion brought millions to the streets, in what became the biggest antiwar demonstrations in history.

Ultimately, however, these efforts failed to stop the invasion. Even worse, two decades of antiwar organizing and activism since have failed to significantly alter the trajectory of U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East, which, despite its unpopularity, continues on a path of futile and bloody “forever wars.” The most recent episode is the U.S.-supported Israeli annihilation of the Gaza Strip, playing out even as we speak.

Polls show that most Americans are against involvement foreign wars. Yet antiwar movements, heavily coded as left-wing, have failed to generate a critical mass of support needed to change U.S. foreign policy. It is worth reflecting on this mismatch between potential and outcome.

I believe that a significant shortcoming of progressive antiwar movements has been their failure to frame their arguments in terms of American nationalism and interests, instead preferring moral condemnation and promotion of revolutionary theories like settler-colonialism that often indict America itself by implication. These messages do not seem to resonate outside a core base of leftist supporters, and thus never actually change the political dynamics in the U.S., let alone stop the wars. Progressive moral denunciation has become merely the expected background music to each new episode of meaningless slaughter.

Something needs to change, and I believe that the past can offer some guidance. Surprising as it may sound, some of the most strident, unapologetic, and coherent voices of opposition to the 2003 invasion of Iraq came not from the left, but from the right. For a number of reasons, I believe that it is this conservative tradition of antiwar activism, nationalist in character, that has the potential to generate the critical mass of public support needed to impose a course correction on U.S. foreign policy. At the very least, conservative antiwar nationalism needs to be a critical component of any coalition to change U.S. foreign policy, tactically allied with progressive movements who may differ with them on other matters, but share the same desire to restrain an out-of-control and unaccountable D.C. foreign policy establishment.

Some left-of-center people are skeptical of appealing to conservative nationalist sentiments, out of fear that it will open the door to some kind of fascist reactionary movement. I think such fears are overblown, and sometimes deliberately exaggerated by a hysterical press. But on a more basic level, to be successful an antiwar movement needs to draw from the biggest tent possible. That means compartmentalizing differences and eschewing needlessly polarizing messaging in order to focus on a shared goal.

In this case, the goal is the very worthy one of ending our involvement in futile moral crusades that do nothing for America’s interests, yet leave an endless trail of grief, waste, and hatred in their wake. If stopping a possible genocide means bringing Cornel West and Tucker Carlson together onto the same stage, under the same flag, that is not some kind of sacrifice or betrayal. Given the stakes, its the bare minimum that any serious antiwar movement must be doing.

A National Interest

Like most people in the world, the average American is generally nationalistic. They may harbor complex sentiments about history, but very few actively reject the country in which they live. As such, appealing to them on the basis of their national identity and interests is an obvious way to get them to support or oppose a given policy. It is surprising that progressives do not do this more forthrightly but there are deep ideological reasons for their hesitance.

Because of its origins in the internationalism of the Cold War, which foresaw a unity of peoples transcending borders, the global left tends reject the idea of nationalism. In some cases, leftists even balk at the idea of appealing to the public on the basis of national interest at all, preferring instead abstract moral arguments and promises of future transformation. It’s quite rare that you will see American flags at an anti-war protest, for example. Yet such flags will be abundant at protests calling for blank check U.S. military aid to Israel, involvement in the Iraq War, or the promotion of other causes probably at odds with U.S. interests, as well as the sober guidance left behind by its founding statesman.

This eschewal of nationalism is unfortunate because leftist antiwar movements really have a strong case that they are fighting to defend America’s national interests. They defend America’s interest not seeing its resources wasted, fiscal priorities upended, reputation tarnished, and the lives of its young men and women needlessly sacrificed. These remain the core selling points of a bipartisan antiwar movement that would resonate with most Americans on nationalist terms.

At the time of the Iraq War, the most successful exemplar of a nationalist antiwar position came from then-Congressman Ron Paul. Unlike liberal opponents of the conflict, who felt compelled to engage with supporters of the war on their own terms and found themselves sucked into losing debates about Saddam Hussein’s human rights record, Paul simply denounced the idea that the U.S. should be getting involved in affairs abroad that did not directly affect its security.

Radically, at the time, Paul even empathized with the perspectives of those who were being killed and occupied by the U.S. government despite committing no crime and posing no threat to Americans. He was able to do this because he rejected the liberal internationalist worldview that judged other cultures according to its own standard, and simply placed himself in the shoes of Iraqis as a fellow nationalist and patriot.

“Our military presence on foreign soil is as offensive to the people that live there as armed Chinese troops would be if they were stationed in Texas,” Paul said. “We would not stand for it here, but we have had a globe straddling empire and a very intrusive foreign policy for decades that incites a lot of hatred and resentment towards us.”

As a young person I was enraptured by this antiwar congressman. I even dutifully went out to buy and read his libertarian political manifesto, “The Revolution,” despite suspecting that I would disagree with many of its economic and political arguments.

I wasn’t the only one. Paul became genuinely popular with a huge range of people, including self-identified leftists, liberals, and conservatives, as well as people of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, who were searching for a coherent language to express the depth of their opposition to what was happening in Iraq. His opposition to the war was patriotic, and made use of all the traditional aesthetics of American nationalism in order to appeal to as broad a camp of people as possible. I’m not a libertarian or a nativist, but my appreciation of Paul’s unapologetic antiwar stance, as well as his articulation of the role of civil liberties and the U.S. constitution in actually protecting domestic freedoms, has influenced my political views up til the present day.

But Paul’s story was also a cautionary tale about how cultural issues can be used to divide and destroy a coherent antiwar movement. As he grew in appeal, the congressman came under attack by the press for allegedly associating in the past with white supremacists, in a manner similar to other antiwar conservatives like Pat Buchanan. These attacks did not really dim his appeal to myself and many other young, non-white fans of Paul who were focused on his opposition to the war and willing to hear him out about his past. But they struck a mortal blow against his burgeoning popularity.

The polarizing charge of racism was used to silence Paul on behalf of a liberal establishment that never similarly defined itself as racist, even as it continued with a project of murdering and displacing millions of brown-skinned foreigners. It would not be the last time that cultural fault lines were targeted to break apart any challenge to an abysmal foreign policy status quo. In fact, such attacks continue to be used today to demonize any attempt at building a broad tent, or allying with people across cultural and ideological divides.

To be successful, a real antiwar movement needs to be willing to steel itself against such charges. It must reject the impulse towards being shamed and imposing a “cancel culture,” and instead focus on emphasizing unity, ideological indulgence and forgiveness, and shared material interest. Such unity may even require rallying around something as unfashionable as a national flag, shared responsibility as taxpayers, or upholding the importance of holding citizenship in a country that is supposed to transcend race and ethnicity.

Aesthetics and Ideology

The Koch Brothers and Soros Foundation both fund the restraint-focused Quincy Institute, so there is clearly latent financial and institutional support that would exist to support a popular antiwar movement. The strongly expressed desire among Americans from both parties to stop getting involved in foreign wars should be ripe territory for such a movement to emerge. Yet, despite the accumulated fatigue of two decades of conflict, progressive antiwar movements have failed to capitalize on American antiwar sentiments.

Part of the problem is structural, based on lack of organization. But another serious impediment is a deep cultural schism that prevents the identification of shared interests among America’s antiwar majority. Whereas the pro-war party is bipartisan, the antiwar party is divided and disunited. Right-coded antiwar movements are sometimes racially exclusivist in practice, as Donald Trump’s dishonest but revealing campaign against “endless war” proved to be. But the inability or unwillingness of antiwar movements on the left, which have an abundance of youth energy and street power, to frame their arguments in terms that are appealing to those outside of their own base, including nationalist sentiments popular among many Americans, is also a serious missed opportunity.

Progressive movements have two major problems in reaching critical mass. One is that they have adopted an aesthetic and language that is unlikely to appeal to a majority of Americans. The other is that they mostly remain trapped in the same interventionist Cold War paradigm as the liberal establishment that they chastise. Let me explain the latter point first.

The ideological premise of American foreign policy today is what you could call liberal internationalism, or, more pejoratively, liberal imperialism. It is a crusading, missionary ideology that suggests that the U.S. has not just an interest but a moral mandate to order and judge the affairs of the rest of the world, which it expects to become as socially, politically, and economically liberal as the United States. The problem is that the vast majority of the world, particularly the Global South, is far less liberal than the United States, and might even be deemed racist, homophobic, reactionary, or worse by American standards if one chose to do so.

When you put these conditions together you have a scenario that justifies potentially limitless American empire. For many years, it was argued, both in bad faith and with sincere conviction, that the U.S. needed to go to war in the Middle East to uphold women’s rights, make sure that local leaders were elected, and protect minority groups. These were just a few of the arguments that were tossed around by pundits and politicians to justify war when speaking to the public. Today, it is still argued with complete seriousness that because Tel Aviv has gay pride parades and in Gaza they are forbidden, this rationalizes heavily arming the former to eradicate the latter.

One of the ways that leftist antiwar movements have been neutralized in the past is by exploiting the fact that leftism, like liberalism, is global in outlook and also considers itself to have a mission to the rest of the world. Leftists do not have an inward-looking perspective, but also seek to effect a global transformation in values. No less than liberals, if they ever came to power, leftists would have to make hard choices between their universalism and the world as it exists. Would a progressive U.S. president deal with the Taliban, or would they feel compelled to use sanctions or violence to compel them to change their stance on issues likes women’s rights and religious freedom? Should the U.S. work with dictators who suppress their people so long as they also stay out of our affairs, or should we confront them in the name of our own moral values?

From a progressive perspective, there are no clear answers to these questions. Indeed, leftists are often successfully browbeaten over such issues because they fundamentally share the same universalizing outlook as their liberal rivals.

A conservative antiwar nationalist would see no contradiction. To them it is obvious that our interests do not go far past our own borders. The clearest response to liberal imperialism is thus a nationalist one: How other societies order their affairs has nothing to do with us. As long as they leave us alone, their own culture and style of government offers no invitation to get involved in their affairs. Going further, a real nationalist is primarily concerned with their own problems, does not obsess over judging the affairs of others, and actively works to stay out of distant ethnic and religious conflicts that have nothing to do with them. This is a fundamentally inward-looking worldview that forgoes missionary activity but makes avoiding unnecessary wars very easy.

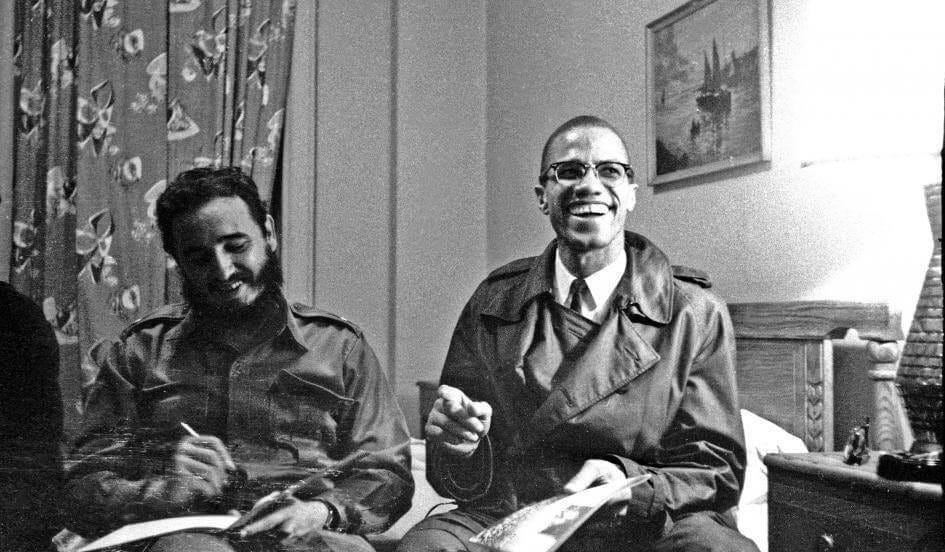

The conflict between peaceful nationalism and often-warlike internationalism also has aesthetic implications, which is another area where left-coded movements have limited their own appeal. The aesthetics of the Cold War internationalist left were captivating to many people around the world, and one can see continued homages to it from young people in progressive social movements. I understand why people are enthralled by glamorous images of Fidel Castro hanging out in a New York hotel room with Malcolm X, or Gamal Abdel Nasser striding across a podium to shake hands with Jawaharlal Nehru. But politically speaking, the movement that those people represented is simply defunct. That is especially true in the Global South which is becoming more nationalistic today, not less.

In the 1960s, it made sense for leftist antiwar movements to adapt an anti-nationalist stance, because they were working to appeal to a global communist movement that shared their international perspective. But no such movement has existed even in theory since the end of the Cold War. In that sense, if one is trying to appeal to the American public to change its voting habits, or confront the ruling establishment over its ruinous foreign policy, it is obviously self-marginalizing to not harness what actually exists, which is their nationalist sentiments.

If you want to effect political change and gain popular support in the present moment you need to use the tools that you have in order to win people over. That may mean downgrading the rhetoric and aesthetics of global revolution and giving more space to the American flag, the Founding Fathers, the Martin Luther King monument, and other symbols of American nationalism more likely to be associated with the center-right today. It also will likely mean talking more about wasted taxes and government corruption rather than loftier ideas like establishing global justice, reversing colonialism, or universal human rights. These are the kinds of messages that are more likely to resonate emotionally with a majority of voting Americans, including antiwar conservatives, who, out of desperation or misguidance, have most recently taken Donald Trump as their own antiwar lodestar.

Our Own Garden

Part of the challenge with building an alliance with conservatives against war is that the United States today does not have an actual conservative political party. The Republican Party, despite its branding, is better described as a right-wing liberal party that shares most of the same baseline assumptions about the world as its Democratic rivals. The mainstream GOP supports an ideology of global empire, including the use of force to make other countries adapt to America’s liberal social, political, and economic values. I’m not against these values, and indeed enjoy many of them. But it is obvious that the best way of convincing others of the American way of life is to be to a good exemplar of its values at home, rather than using sanctions, violence, or other tools of coercion to impose them on others.

This is a fundamentally inward-looking, nationalist antiwar argument. It is one that you might be equally, or even more, likely to hear in the pages of The American Conservative than in Jacobin. To really make change, there needs to be a way to wed the youthful energy of progressive antiwar activists, with the ideological rigor, patriotic aesthetics, and patient temperament of old-school American conservatism. I understand people’s hesitance to get into a broad ideological tent with people who may disagree with them on issues like abortion, immigration, policing, and the climate. But if stopping a crime no less grave than genocide is really an urgent priority, there is no other option than at least partly embracing conservative nationalist arguments, tactics, and symbolism to rally a critical mass of the public.

Any criticism I may have of left-coded antiwar activism is not due to personal objection to the majority of activists, who I believe are sincerely driven by a desire to establish a more just world, but rather due to my experiences as both an observer and participant in such movements in the past.

I hope future generations will not make the same mistakes as their predecessors who tried and failed to stop the Iraq War and many other conflicts. My advice to them is really quite simple: Rather than trying to appeal to revolutionary ideas of transforming society in order to stop wars, you should focus on a basic message that most Americans will likely agree with: We should not be wasting our tax money, the lives of our young men and women, and our precious time and energy on dubious and ill-defined foreign conflicts that bring us no benefit.

War may sometimes be necessary to defend our safety and interests. But America is in fact a very safe country, separated from the world’s problems by two giant oceans. It does not need to involve itself needlessly in the bitter conflicts of others. The fact that foreign countries may be more socially conservative than ours offers zero justification for going to war, let alone despising them. If we want to make the world a better place, we should focus on tending our own garden, rather than intruding upon others.

A winning antiwar message would probably have to marry the non-interventionist policies of Bernie Sanders with the flag waving aesthetics of Donald Trump. Given the stakes, such an approach should be embraced embraced without apology. If it means trade-offs on other subjects, which it will, then it is an opportunity to put ones own beliefs to the test about how important ending America’s forever wars really are. After spending my entire adult life watching these wars continue unabated, leaving endless suffering in their wake, I would venture that the cause is worth it.

As strong as it seems from the outside, the D.C. foreign policy establishment is in fact a small, brittle community. They mostly get away with murder because of how little scrutiny their actions get. Yet after serial missteps, there are now visible embers of a backlash against them growing in the American public. The only question is who will be able to blow those sparks into a flame strong enough to burn down this rotten consensus, which has outlived its usefulness to both the American people and the world beyond. I hope that young Americans from all backgrounds will think hard about their strategy for accomplishing that.

Excellent overview, Hussain.

We tried this. Antiwar.com and libertarians WERE part of the anti-Iraq War movement. So much so that Ron Paul largely ran his campaigns by leaning hard on anti-interventionism, which attracted people across the spectrum. What did we get for this? Eventually he and others like him turned into the loons calling Obama a Socialist, and red-baiting everything left of center.

Simply put, the complete schism between public opinion and public policy has made antiwar organizing almost pointless. It is much easier to galvanize people to vote on what are considered "domestic" issues. And on those matters, there's no nexus for organizing with the right.