On Hindutva

Reading history and V.S. Naipaul

Many years ago, while reading an otherwise unremarkable collection of essays on the future of the Anglophone world, I came across a prediction that gave me pause. While discussing the long-term impacts of immigration, the author, who accepted migration as a political inevitability, casually stated that one day immigrants from the Indian subcontinent would import the famously bitter religious conflicts of their homelands to the cities of the West. It was a suggestion that I found absurd at the time. I grew up in a city filled with the children of Pakistani Muslims, Indian Hindus, and Sikhs living in close quarters. The painful histories of India and Pakistan were of little concern to this generation, who were focused on immersing themselves in the opportunities, distractions, and new identities found in the countries to which their parents had immigrated. Once the politics were stripped away, they even found that they had a lot in common, including a shared interest in resisting racism from the broader society. The notion that these same hyphenated Westerners and their offspring, living in England, America, Canada, and Australia, would ever hate each other over their identities, let alone mirror the violent politics of the Indian subcontinent, struck me at the time as absurd and even a little offensive.

I thought of that essay and my original reaction to it last year, while reading about violent clashes between young Hindu and Muslim men in the British city of Leicester apparently triggered by sectarian hatred. That unrest was a preview to an escalating series of confrontations between Sikh nationalists and supporters of the Indian government that have taken place this year from Canada to Australia, some of which have risen to the level of international incident. I won’t bother recounting all such outbursts like this that have taken place of late, including those in the United States. But there have been many of them, and it clearly has a connection with the recent growth and spread of Hindutva in the subcontinent.

If you’ve been familiar with my past writing will know that I have devoted a lot of time trying to understand and critique Islamism, both in its moderate and radical forms. The growing salience of Hindutva, which is both similar and different to Islamism for reasons I will discuss, merits attention as well. I am not enamored of Hindutva, at least in its present iteration, partly because it is an active source of terror for friends and relatives living in India. That said if one argues that movements like the Muslim Brotherhood should be treated with nuance and understood on their own terms, the same consistency has to apply to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and other Hindutva organizations. To help with this, I thought it would be helpful to look back on the writings of a man who was a huge influence on me as a writer, yet who did as much as any contemporary Western intellectual to will into existence the Hindutva tide now sweeping India.

Bitter Medicine

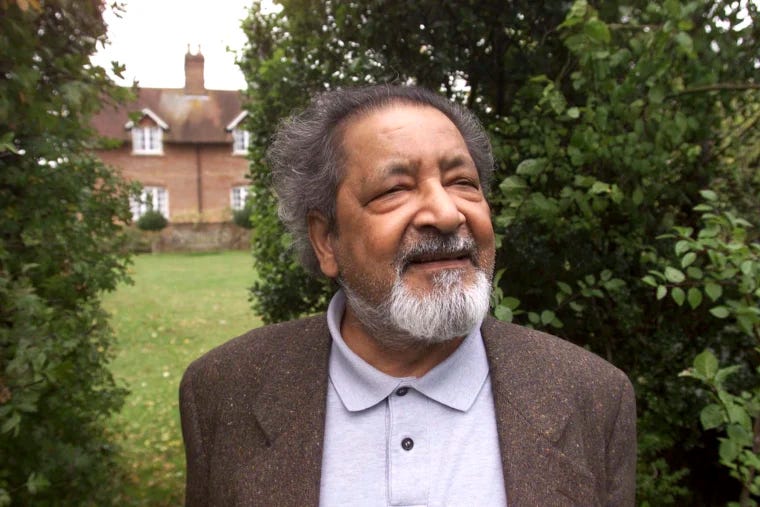

A Trinidadian by birth, V.S. Naipaul spent his life as an itinerant wanderer and journalist in the developing world. He wrote a trilogy of books about India documenting his travels in that country over his lifetime. India: A Million Mutinies Now, was by far the strongest of the three and merits reading even today. The trilogy detailed Naipaul’s own impressions of India as an outsider, starting off starkly negative, and growing more optimistic over time about its future. In addition to brilliantly diagnosing India’s current conditions as a journalist and interviewing ordinary people from across the breadth society, Naipaul also helped popularize a dark, sectarian reading of Indian history that challenged the overly upbeat version of the country’s past promoted by post-independence historians. This history is at the core of Hindutva today, which is a movement in which Muslims unfortunately play an indispensable starring role.

In Naipaul’s view, Indian Muslims are at best alien interlocutors in what is essentially a Hindu civilization. At worst, they are its eternal enemies. Many people make the short step over to this conclusion. Indo-Islamic dynasties in the subcontinent, which were ultimately imperial in nature, also left behind architectural, linguistic, culinary, and aesthetic legacies in India that have shaped its culture in an indelible manner. According to Naipaul, the role of these Muslims and their descendants in India was totally negative over the course of an entire millennium. In order to liberate India on behalf of its indigenous inhabitants, who are only Hindu and members of other smaller religions plausibly cast as Hindu, Muslims must be overthrown, crushed, and eradicated. On this basis, he celebrated the mob destruction of an ancient mosque in the city of Ayodhya in 1992 that was alleged to have been the birthplace of the Hindu god Ram. In contrast to the misrule of Indian Muslims, Naipaul approved of British colonialism, which he claimed had invigorated the Hindu majority of the subcontinent and set the stage for their later renewal.

Reading this was all was very surprising to me. The idea that subcontinental Muslims who had lived there for over a thousand years were actually “invaders,” an idea that is now a routine part of political discourse in India, is not one with which I was familiar. This idea of eternal Muslim (and to an extent Christian) foreignness to India makes up one of the core ideological tenets of Hindutva and goes back to events believed to have taken place in the mists of time around 1000AD, or even before that. Historiography is an imperfect art even in the present day, but, as the story goes, around that time Central Asian warlords espousing Islam engaged in plundering raids in Northern India that resulted in the deaths of many Hindus and the pillaging of temples. After the eventual establishment of Islam in the subcontinent through a mixture of conquest, trade, and proselytization by local saints, later medieval Muslim kings also engaged in discrimination against Hindus, particularly the 17th century Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.

Pretty much all of the historical episodes of grievance that undergird the Hindutva view of the world are centuries if not over a millennium old. One would imagine that such things would be treated matter of factly as ancient history, which they are, yet they seem so viscerally alive that they may have taken place just yesterday. Aurangzeb himself is so regularly denounced by BJP politicians that one could be forgiven for thinking that he was running as a candidate in the 2024 Indian elections.

To be fair, the Hindutva view of history is based on events that were both real and imagined. Yet they are also unfamiliar and alien to the overwhelming majority of subcontinental Muslims. In the unlikely event that they are even aware of it, the crimes of the Central Asian warlord Mahmud Ghaznazi in the 11th century play no role in contemporary subcontinental Muslim self-conception or identity and its very hard to argue that they should somehow be blamed for it. I would wager that I’m in a pretty high percentile of educated people, and these resentments were not something known to me, nor was the fact that I was apparently an “invader” in the Indian subcontinent which is the only place on earth to which my family can trace its ancestry. If you want an example of this dynamic of fierce accusation and defensive bewilderment, I encourage you to watch the below video of a 1957 high school debate in the United States that includes an exchange between a right-wing Indian Hindu and a Pakistani Muslim student.

Is Hindutva Sustainable?

One of the uncomfortable facts of history is that the global spread of liberalism over the past two centuries was closely tied to the project of American and European empire. While these empires did not always behave liberally, they justified themselves using liberal premises and helped foster classes of likeminded peoples around the world. As the great tide of Western empire has receded in the face of a reemergent Asia, liberalism, rather than laying permanent roots, has gradually receded along with it. In places like the Middle East and South Asia, we have begun to see what was submerged underneath the ideological waters for all those years: religious idealism and ethnic tribalism.

India had a stronger liberal tradition than most developing countries. The genius and charisma of men like Jawaharlal Nehru and Mohandas Gandhi meant that the process of liberal decay took longer to play out in India than in places like Egypt or Pakistan. Yet the decay has taken root. Hindutva, through the vehicle of the BJP, has capitalized on the failures of the once-mighty Indian National Congress party. The latter is now demonized as elitist, corrupt, culturally alien, and the lackey of foreign powers. On a structural level, the Congress Party also today resembles the patronage-based dynastic parties of Pakistani politics, whereas the BJP can credibly claim to be more meritocratic, at least for Hindu members. Their strategy of polarizing Indian Hindus against Muslims makes sense strategically, as whipping up the hatred of 80 percent of the population against 20 percent makes for sound electoral math.

It is unclear what a Hindutva foreign policy will really look like. Due to Islam’s character as a universalist religion, Islamism, when it emerged from the wreckage of the Middle Eastern left, tended to have transnational ambitions. Hindutva, in keeping with Hinduism’s non-proselytizing, India-centric worldview, is a blood-and-soil ideology that has little use for global ideological ambition. However much blood it may spill inside India, this parochial focus means that Hindutva, despite its post-colonial suspicion and hostility towards Westerners, has a good chance of avoiding a major clash with the West in the near the future of the kind that doomed the Islamists. What both movements do share in common aside from a basic chauvinism is emotional immaturity and low self-esteem among rank-and-file that can manifest in hysterical and occasionally murderous hypersensitivity to slights. This is an area where the volatility of Hindutva proponents can undermine India’s soft power and diplomatic relations.

While they may be able to stay on decent terms with the West which desires India’s support to bandwagon against China, what will be more difficult for Hindutva will be managing its relationship with the Islamic world. India has warm historical relations with most Muslim countries aside from Paksitan, going back to the leadership of Nehru. These ties have become more uneasy as India has transformed in recent years. Hindutva’s antipathy towards Muslims is technically focused on subcontinental Muslims. But once people get intoxicated on hatred it’s a bit difficult to keep it limited and focused. The advent of global communications technology has created many awkward incidents in which the extreme anti-Muslim speech of Indian activists and political figures has been broadcast to the entire world, generating embarrassment and offence among India’s diplomatic partners. Given that the world at large, and particularly Asia, is very Muslim, a national ideology defined in terms of vocal animosity towards Muslims is going to run into very obvious complications and may hamstring India from fulfilling its destiny as a cosmopolitan economic and political power.

The leadership outlook for Hindutva parties is another important issue. Due to its meritocratic internal culture, the BJP is able to promote talented members from within its ranks who can rise to the top on their own merit, rather than through nepotism and patronage. Narendra Modi himself is a former provincial governor of humble background who was once banned from entry to the United States for his involvement in massacres of Muslims in his home state of Gujarat. Despite that, today even his most vociferous liberal critics acknowledge that he is one of the most popular elected leaders in the world. One can indeed understand why Modi is popular among many Indian Hindus. He shows little sign of personal ostentation, appears sincerely concerned with the welfare of his coreligionist citizens, speaks with measured charisma, and can credibly claim based on his upbringing and personal style to be a son of the Indian soil. Contrast this with the lavishly sleazy style of Pakistani politicians, whose corruption is the stuff of legend and who go out of their way to culturally distance themselves from the people that they rule by publicly portraying themselves as ersatz Americans. Even in issues as seemingly trivial as speech and style of dress one can see an obvious difference between Modi, and, let’s say, Asif Zardari. However much they dislike him, many Pakistani nationalists wish dearly that they could have a Pakistani equivalent of Modi in their own country.

There are individuals waiting in the wings of the BJP who are far more extreme than Modi and could push the limits of what India’s partners find publicly tolerable. Among them are his own Home Minister Amit Shah, as well as a Hindu monk and former vigilante named Yogi Adityanath who today governs the massive northern state Uttar Pradesh and whose public attitude towards Muslims makes Modi look like Mohammad Iqbal. Governorship of Uttar Pradesh is historically seen as a stepping stone to higher offices, and, given what is going in that province at present, one can imagine what an India governed by Mr. Adityanath may look like.

A Perennial Tradition

I learnt alot about Hinduism from a Kashmiri Muslim friend whose family suffered a lot in India, but who had studied the Indic traditions alongside Islam and insisted that they contained a lot that was both true and valuable. Hinduism indeed does contain many fine precepts, as evidenced in the lives of great men like Swami Vivekananda and Rabindranath Tagore, as well as many ordinary Hindus whose good nature and decency are testaments to the worth of their tradition. People who dismiss Hinduism based on backwards popular practices of some lay Hindus (as though Muslim and Christian laypeople lack for backwards practices) ought to study some of the religious philosophies of Brahmin Hinduism with an open mind. Therein they will find an admirable spirituality and rationality at the core of their worldview, as some Muslim scholars and dynasts themselves concluded many centuries ago in India when they first studied them.

Although Hindutva in its present iteration as an anti-Muslim ideology is morally objectionable, it is not wrong for Hindus to want their religion to be respected and welcomed in the public sphere. If one can imagine a different version of Hindutva that satisfies people’s desires for respect and fulfilment without creating a new outcaste in the process, there would be nothing wrong with that. Nor should ordinary Hindu religious practices be demonized as Hindutva extremism, as some liberals have occasionally done. Given the negative history of Islamism, including in Pakistan which itself is a generally intolerant society and whose creation helped lay the seeds for Hindutva reaction, I’m no longer confident that any peaceable ideology can be formed on any modernist-religious basis. Yet one has to hope for pragmatism and forebearance to win out.

Naipaul, despite his support for Hindutva, once observed that “the past has to be seen to be dead; or the past will kill.” The past is very alive in India today, particularly the ancient and medieval past. Such deep hatred over history seems capable of justifying the worst things that human beings can do to one another, including recent campaigns by Hindutva activists to defend rapists and murderers accused of crimes against women and even children deemed guilty of having been Muslim.

The world has seen similar things before, including in the former Yugoslavia where old hatreds emerged from the deep thaw of Communist rule to inflict a genocide unlike anything Europe had seen since the Second World War. I have spent a lot of time in Bosnia over the years. On one trip, I went with a Bosniak friend to visit their hometown that had been ethnically cleansed by Serb nationalists during the war. The violence there had been particularly gruesome and personal. His local high school, which we stopped by, had been transformed during the war into a center where Bosniak women were brought by their former neighbors to be raped during the conflict, while their husbands and sons were tortured and executed in the industrial parks and office buildings on the outskirts of the town. The town today is an eerie, ethnically homogenous shadow of its former self, cleansed of its former Bosniak and Croat residents.

My friend was a lucky one: He survived and became a soldier in the nascent Bosnian Army, where he was wounded in a mortar attack that left him in a coma for nearly a year. He is still traumatized by the fate of his hometown, and trying to process how it all could have happened. About the subterranean resentments that had one day erupted and turned neighbors and former schoolfriends into mortal enemies, he told me: “All that hatred, we never saw it. These people were our friends and our neighbors. Suddenly, they turned and told us that we were guilty. Why? ‘Because of history.’”

No More Talk

After a lifetime of berating Muslims and blaming them for all the ills of modern India, Naipaul ended his life married to a Pakistani woman whose family was tied to the country’s notorious Inter-Services Intelligence agency. If there is a lesson in that it is that real-life is inevitably messier and more complex than the sharp lines seemingly drawn by history and politics. From my experiences trying to engage with supporters of Hindutva online and in the real world, I haven’t found them to be particularly reasonable or open to compromise, and that also reflects in their politics. I have no illusions that many of them will appreciate an article such as this one, and have found that attempts to treat them with nuance and understand them on their own terms actually enrages them even more. This fury may have consequences for the world in the years to come. The looming threats of climate change, water shortages, and the presence of nuclear weaponry lead me to believe that the fraternal hatred and violence of the subcontinent has still not reached its apex. The combination of aggressive Hindutva in India and bellicose military-led Islamic nationalism in Pakistan may be enough to bring about something truly terrible in the coming century.

The Anglophone world is also becoming more Indian and Pakistani by the year thanks to immigration. I still believe that at least in the United States the engine of liberal assimilation can give people new identities when they arrive here that are compelling enough for them to leave behind the insoluble problems of the old world. Yet that’s hardly a given. Islamism had a powerful, mostly negative impact on the world in the 20th and early 21st century. As Naipaul himself would have likely acknowledged were he alive today, the turn of Hindutva, whatever it has in store, is just beginning.

My mind expands when reading your essays. Thank you.

Great stuff