Journey to the End of Islam

Reflections on performing the umrah pilgrimage and modern Saudi Arabia

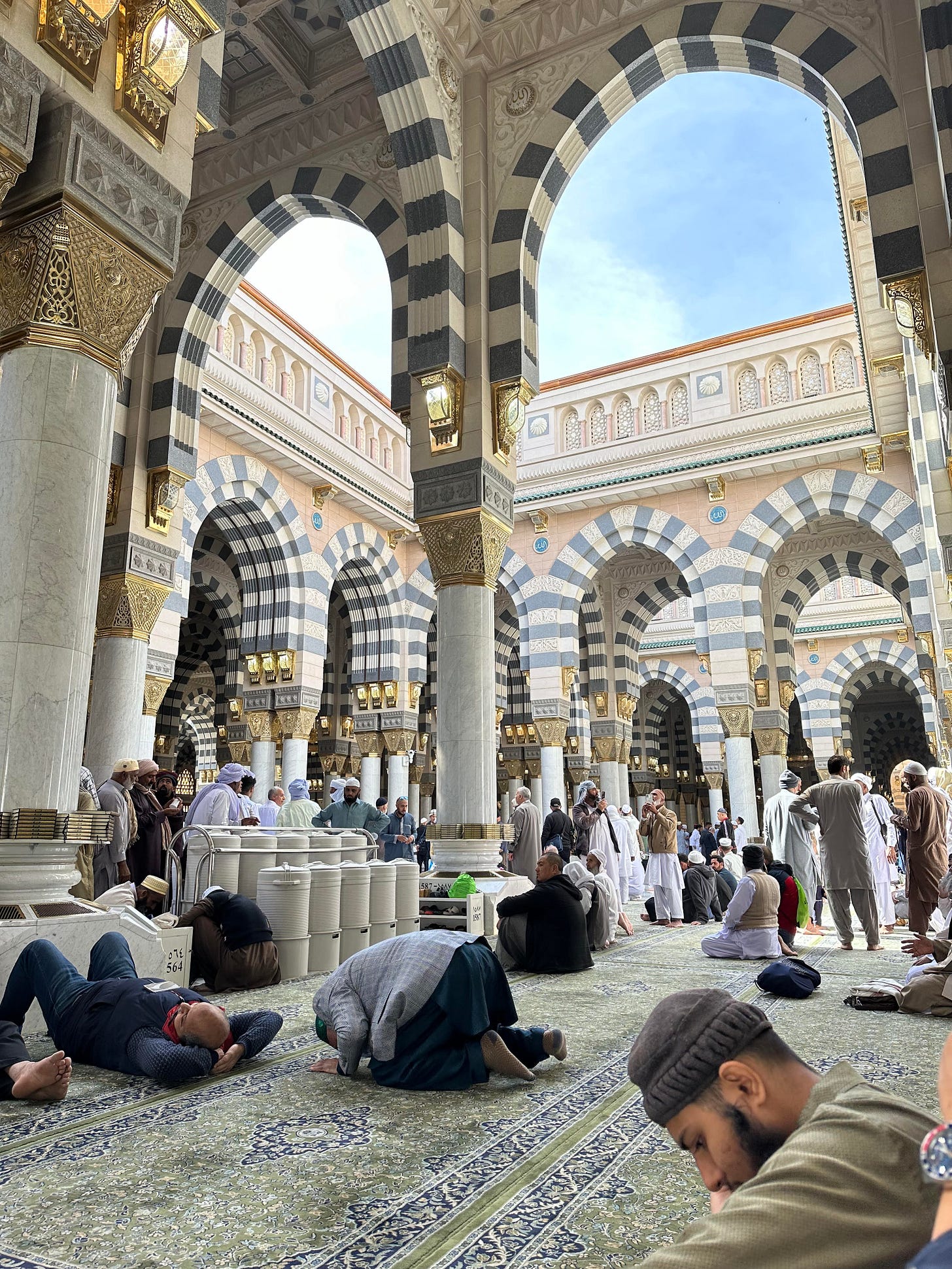

The Prophet’s Mosque in Medina

When I was a child, my family lived in the city of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. My father was a Pakistani expatriate worker at the time employed in an establishment then known as the al-Harithy Hotel. My memories of this time are a sun-drenched haze. But the period has always loomed large in the memory of our family. My father described his Saudi Arabian sojourn as the best time of his life, in part because it was the only time that he felt he had any money. The good times eventually came to an end when he offended a powerful person at work by crossing some invisible red line of decorum and obedience as a foreigner. What happened next was never fully explained to me, but the consequences of this incident spooked him and my mother enough that, even after his Saudi sponsor intervened on his behalf to defend him, they began urgently casting about for immigrant visas to Canada, the United States, Australia, or wherever else would take us. That’s how I got where I am today.

My father passed away last year suddenly at the age of 69. Along with some other changes in my life, his passing somehow made it feel logical for me to return to Saudi Arabia. I came to make a few personal calls on relations, but also to visit the cities of Mecca and Medina and perform the umrah, the minor act of religious pilgrimage in the Islamic tradition, on his behalf.

Although I came as a simple traveler and religious pilgrim, I couldn’t help but also observe the country with the eye of a journalist. Suffice to say, I was equal parts enchanted, disturbed, and intrigued by what I saw on this journey. I wanted to share my account of this trip, which, in addition to serving a spiritual purpose for myself, was eye-opening in many ways about the state of modern Islam and the visible changes now taking place in Saudi Arabia. My interest is neither to preach nor wound, but simply give an honest glimpse of a people still groping their way towards a healthy synthesis between tradition and modernity.

Heart of the Medina

I took a red-eye flight from John F. Kennedey International, connecting in Jordan, and arriving late in the evening in the city of Medina. The first thing you notice when you arrive at Medina International Airport, besides the morale-crushing immigration lines and dim 1980s-style airport lighting, is that all the people working at the customs posts are women. When my mother lived in the country she spent her entire life at home taking care of my infant self, since, at the time, the very concept of women in the workplace was considered risible. The exclusion of women from public space had long been one of the infamies of Saudi Arabia. But the Saudis are clearly making up for lost time. Starting from my arrival at the airport, one thing I noticed throughout my time in the country was that women were working in public facing jobs everywhere. Not only were they working, but they mixed naturally with male colleagues and clients, and generally came across as the most diligent, confident, and assertive people you’d interact with in any context. This is not just a 180 degree change from the time my family lived there a few decades back, its a revolution from even a few years ago.

I arrived in Medina first because of its importance in the Islamic tradition, but also because of how highly people I know have spoken about the city. Medina is the burial site of the Prophet Muhammad, and the place where many of the formative events of his life and career took place. People have always talked about it to me with starry eyes, describing it as a city that naturally exudes a sense of serenity to those who visit. Songs have been composed in multiple languages as tributes to the virtues of Medina, said to be the sweetest city on earth. My father, generally a skeptic of anything to do with metaphysics, had told me the same.

I took a taxi into the city center in the middle of the night, dusting off my rusty formal Arabic with the cab driver who, like many other locals I met, bragged to me about how many generations of his family had traced their roots to this place. Downtown Medina does not feel ancient, but it also does not feel like any modern Western city. It is a city of mid-rise beige marble buildings, mostly hotels for pilgrims, with arched storefronts on the ground floor facing the streets. The traditional old core of the city has been demolished, and few traces of it are visible. But the new marble buildings that have come up in its place do not offend, and fit well with the natural landscape of brown rock and sand. There are no skyscrapers and the structures are all level height. The streets mostly do not feel hostile or overpowering, and at least a few are closed off to traffic. Many buildings even boast tributes to the brown wood panelled windows traditional to the region.

The streets of Medina brim with people from every corner of the world and from every class. South Asians, Africans, Arabs, Chinese, Turks, and many more peoples mill through the shops and mosques day and night. Outside the city center, there are even walkable, newly renovated narrow streets reminiscent of the Greek Mediterranean, lined with small shops selling clothing, incense, jewellery and sweets. Much of the work in these stores is done by Saudis, who take great pride in being custodians of a holy city and providing a sense of direction and hospitality to the endless streams of people from around the world who come to visit. The task is not an easy one. Yet they really do a remarkable job at maintaining a sense of cleanliness, order, and warmth. In the distance beyond the city, standing mutely above all the worship and commerce, one can still see the ancient brown rock hills that loom over Medina, just as they did during the time of the Prophet Muhammad.

In past decades, the Saudi government has been criticized for destroying much of the ancient history of Islam, bulldozed to build hotels, businesses, or highways, or out of religious zeal to prevent people from “idolizing” historical artifacts associated with Islamic civilization. So much of this Islamic legacy has tragically been lost forever, including in Medina. But the present government seems to be trying to salvage what is left in order to generate revenue and increase the attractiveness of the city. I visited a few of these sites, including an ancient date palm planted by the Prophet Muhammad as payment to free a slave who later became the first Persian convert to Islam, as well as an ancient well from which he was known to draw water. The government has put up signs with descriptions of the places, encouraging people to come visit. I saw small groups of visitors from around the world coming to pay respects, but also out of simple curiosity to witness something connected to the life of Muhammad. It was nice.

An ancient date palm in Medina planted by the Prophet Muhammad.

Medina really is the city of Muhammad, and a visitor comes to understand intimately why Muslims hold him in such high esteem. The beating heart of the city is the sprawling Prophet’s mosque, or Masjid-e-Nabawi, an ornate compound where Muhammad himself is buried along with several of his early companions. A visitor to Masjid-e-Nabawi or the streets surrounding it will see something unlike anywhere on earth: People from every corner of the world, drawn from every strata of society, speaking a dizzying array of languages, adorned in an endless kaleidoscope of traditional clothing, divided by class, race, and geography, yet united again by a sense of fraternity and affection centered around this man and the civilization that he inspired, which told them that they were all equals in humanity. The mosque itself is regal and palatial, open night and day with equal rights to its premises held by both rich and poor. I know how poor people in Pakistan live and how many do not even have the right to enter a fancy building, let alone claim their own space there. But in Medina no one can take that right away from anyone. After 1,400 years, the place that Muhammad preached and is now buried remains a giant canopy of love and fraternity under which anyone is welcome to come and sit.

The sense of order and dignity extends well beyond the mosque compound. Despite the crowds that exist throughout the city, there is not the slightest sense of danger, disorder, conflict, or defilement visible anywhere. The city also happens to be an incredible melting pot of the peoples of the world. I was impressed to converse with Bengalis who spoke Persian, Iranians who spoke English, Arabs who spoke Urdu, and all other manners of effortless cosmopolitans. In the Quran, it is said that God made mankind “into nations and tribes, that you may know one another.” You really witness that in practice in Medina. In every interaction, large or small, there is a sense of gentleness and tranquillity. There are still class divisions visible, and some of the noisy chaos of modern car culture penetrated the heart of the city. But it has failed to ruin its essence. A man I spoke with who traced his lineage two hundred years back in Medina, his family having migrated from Afghanistan, lamented to me the loss of some of the city’s old neighborhoods in recent years to development. Yet the real spirit of the city could never change, he added warmly, thanks to the legacy of Muhammad.

After a week in Medina, doing nothing in particular other than visiting sites, strolling the streets, spending time at the mosques, and chatting with locals and pilgrims, I truly understood in a deep way what my father and others had tried to tell me. This is a lovely place, where you feel not just safe but a deep sense of peace. I was very glad that I started my journey in Medina, because what I saw next disturbed me with almost as much force as the serenity I had felt there.

Return of the Mecca

Mecca is considered a religious sanctum, which means that only people who are Muslim are allowed to enter its boundaries. That’s very fortunate, because if the rest of the world were allowed to see modern Mecca it would not paint a very flattering image of Islam or its adherents. Mecca is an ancient city, home to the Kaba’a, the geographical epicenter of Islam. Yet instead of dignifying this inheritance, the city has been transformed into one of the most garish urban areas on earth. The old streets and souks have been dynamited, not to build something noble that still fulfils peoples’ needs, but in order to transform the first city of Islam into a cross between Times Square and the Las Vegas Strip. I’d read a few articles about the commercialization of Mecca, but nothing prepared me for actually seeing how bad it really was.

I have a friend of Chinese background who converted to Islam because of what he felt was the excessive materialism of modern Chinese culture. Suffice to say, he would be very disturbed by what he would see in Mecca. The ancient city has been replaced with endless rows of towering, mismatched hotel buildings, fast food chains, and sprawling shopping malls. The area directly around the mosque feels less like a city center than a gigantic slot machine. The first thing I saw after stepping out of my car was a giant neon Dunkin Donuts sign facing onto the street, assuring all who passed that the worst coffee in America was available at all hours to foreign pilgrim and Meccan alike. A giant Kentucky Fried Chicken, Rolex store, and McDonalds pen the mosque on all sides, which itself looks utterly cowed amid the forest of luxury buildings, multistory malls, and retail outlets that claim every bit of empty space.

I’ve been to the Vatican, the Western Wall, and sacred shrines dedicated to religions around the world. Yet I have never seen anything as undignified as present-day Mecca. To be fair, there was a challenge in reshaping the old city to fit the needs of millions of pilgrims who come there each year to pray, while maintaining a sense of religious reverence. Yet that challenge could not have been failed more spectacularly, forfeited in the pursuit of profit and cashing in on the lucrative real estate around the Kaba’a. The second you step off the grounds of the holy mosque itself, you are immersed, immediately, in a type of gaudy consumerism found only at the most extreme ends of the United States. What’s worse is that this excess is mixed with signs of the crushing poverty that characterizes much of the Muslim world, with limbless beggars and homeless children, many organized by professional gangs, sitting outside of the luxury stores and pleading for money from the shoppers-cum-pilgrims.

An umrah pilgrim dons a simple white robe to symbolize the equality of all mankind in the face of God. Yet Mecca has been rebuilt as a living tribute to grotesque inequality, with the super-wealthy enjoying aerial views of the Kaba’a from swanky accommodations, while the poor sleep on the streets and are bused to impoverished dwellings on the outskirts of the city. There is no serenity in Mecca, just a relentless racket of consumption and exorbitance that assails you from every corner. Any visitor to the city willing to set politeness and pride aside can recognize it for what it is: A living monument to the decline of Islamic civilization. It is one thing to embrace material progress, but what self-respecting people demolishes the treasures of their civilization to build a Hardees?

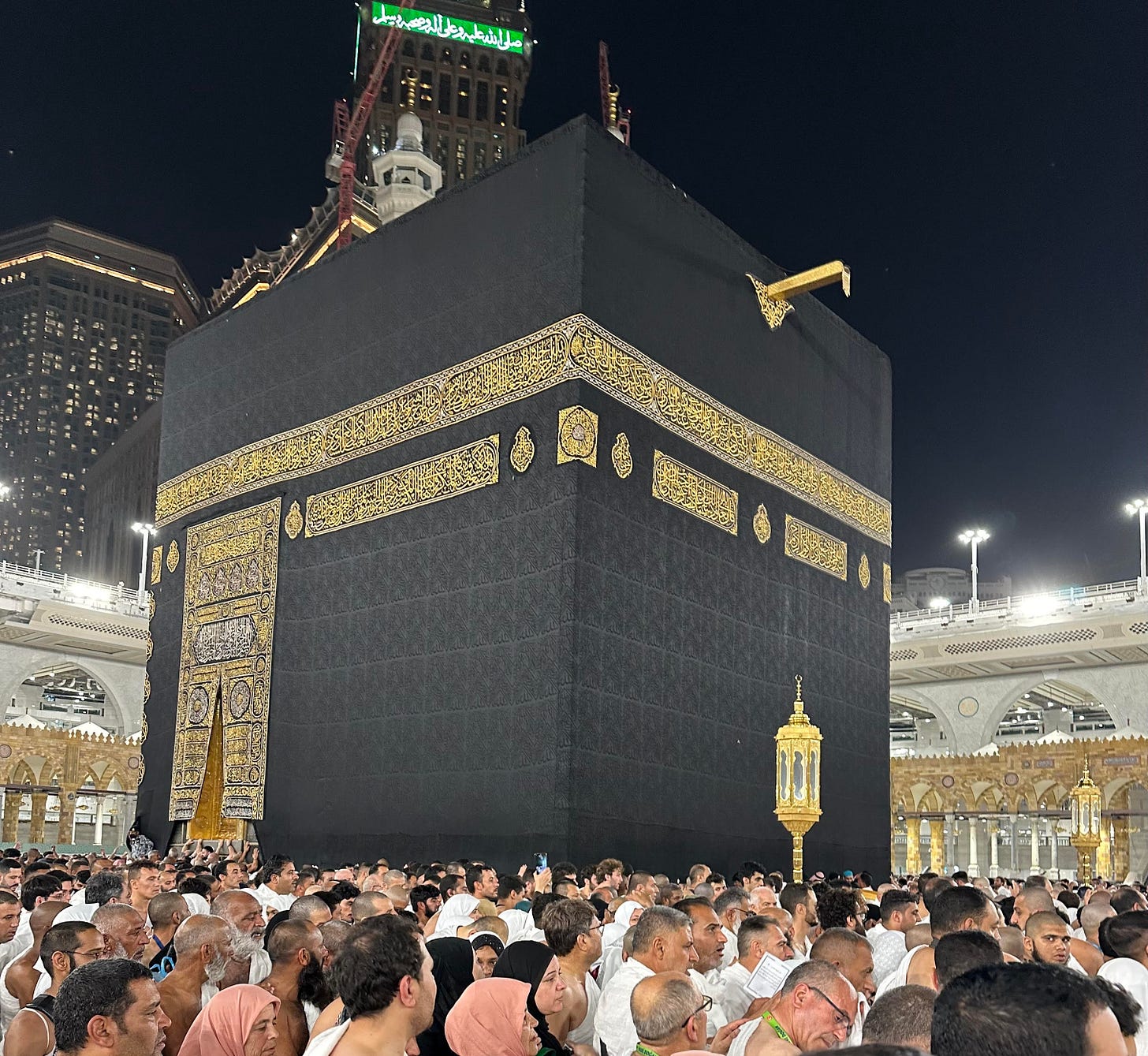

The Mecca Clock Tower hotel and shopping complex towering massively over the mosque.

Walking around downtown, the building that is most prominent is not the holy mosque but the Royal Mecca Clock Tower complex, which looks less like a building than a gigantic neon tombstone. I live in New York City and am not exactly a rube. Yet I’ve never seen a building like this before, and not in a good way. The clock tower and surrounding complex, looming directly over the mosque, are not just huge but Stalinist in proportion. A pedestrian passing by feels simply pulverized. The building, which has now become a symbol of the city on par with the Kaba’a itself, is not just ugly but feels like an insult. Its design reflects none of the styles, or traditions of the Islamic world, nor the philosophy of harmony and symmetry with nature that has been embodied in traditional Islamic architecture for more than a millennium. Instead it looks like a puffed-up attempt to copy Big Ben in London, or the Sun-Life Building in New York, while lacking even the virtues of originality and cultural cohesion that those structures have. One is not reminded of God by looking at such an building, but of the power of materialism, capitalism, and the state. Perhaps that was the point.

Contemporary Mecca gives the impression that a sucking vacuum exists at the heart of a great world religion, with the void filled by the tackiest refuse of American consumer culture. Rather than failing to modernize, Muslims have simply adapted the worst aspects of the modern West, most notably the dead-eyed materialism, greed, and aesthetic chaos. In doing so they have both missed out on the more profound egalitarian values of Western civilization, while also losing most of what was good in their own culture. Given that the Islamic world was once known for its urbanity, it begs the question of how such a thing could have happened. The answer seems to have been an accidental confluence of forces, whereby the religiously and politically important holy sites fell out of control of urbanites in the early 20th century, and into the hands of bedouins who then struggled mightily to grapple with the windfall of the petroleum era. Hence, Mecca.

Years earlier, T.E. Lawrence, who traveled with the Arabs of the region and admired what had then been their honest virtue, predicted in his memoir Seven Pillars of Wisdom what wealth would do to the simple, sustaining culture of such people:

“Had the circumstances of their lives given them opportunity they would have been sheer sensualists. Their strength was the strength of men geographically beyond temptation: the poverty of Arabia made them simple, continent, enduring,” Lawrence wrote. “If forced into civilized life they would have succumbed like any savage race to its diseases, meanness, luxury, cruelty, crooked dealing, artifice. And, like savages, they would have suffered them exaggeratedly for lack of inoculation.”

Given the tacky artifice of the city of Mecca, can one say that the experience of performing umrah has been ruined? Surprisingly, no.

Despite my disenchantment at the city, I performed the umrah pilgrimage twice while in Mecca. For all the terrors that urbanization had inflicted around it, the construction and maintenance of the mosque itself has been done with care. The Kaba’a itself remains an ethereal sight; there is no building like it in the world and I will not forget the first time I laid eyes on it. From the outside, it looks like a hostage of the hideous towers built as a prison around it. But from the inside it is clear that nothing can really overshadow it. From the perspective of the Kaba’a, even the giant clock tower, with its neon green glowing face, looks like a scared monster, pressed back and afraid to come too close. The masses of humanity in devotion, circling around the Kaba’a day and night, making their supplications, calling out praises to God in dozens languages, FaceTiming with their children in every corner of the world, quiet tears streaming down smiling faces, is something unlike anything else on earth. For a few moments, as I was circling it with them, I felt the peace that Muhammad must have felt over a millennium ago walking and meditating around the same spot.

It seems unlikely that the slabs of concrete and excess that symbolize modern Mecca will go away any time soon. But if the Saudi government can invest billions of dollars in building horizontal cities and gigantic cubes, they have the capacity to erase this error and build something that respects and ennobles the religion that has been vouchsafed to them.

The Arab novelist Abdul Rahman Munif, legendary chronicler of the impact of oil on the Middle East, predicted the demise of the monstrous and unnatural urban creations that the petroleum windfall had created in the region. “When the waters come in, the first waves will dissolve the salt and reduce these great glass cities to dust,” he told an interviewer. “In antiquity, many cities simply disappeared. It is possible to foresee the downfall of cities that are inhuman.”

The old Mecca of Muhammad has already been wiped from the face of the earth by construction cranes, dynamite, and bulldozers. One can only hope that the inhuman new one will be effaced in the same way.

If there is one lesson that Mecca today teaches it is the difficulty of reaching inner silence and connection with God amidst the deafening clamor and artifice of the modern world. As I was walking one night back to my hotel, I saw a group of Indonesian pilgrims, striding with slow reverence towards the sacred compound, steering their way through crowds of shoppers, their white robes bathed red from the glow of a massive KFC location built directly across from the mosque. Islamic culture is clearly a shell of what it once was, more of a handmaiden than competitor to the materialism of the modern world. But as long as people like them can still find their way through this maze to meet the divinity alive deep at its heart, the sacred thread is not yet broken.

Red Sea Redux

Saudi Arabia is now well into a third generation of urbanization. According to the medieval philosopher of history Ibn Khaldun, this should be a time that the civilizing impact of city life wears off the harsh edges of the frontier and gives birth to a new culture. The social liberalization now taking place in the country suggests that something like this is starting, albeit in a manner devoid of political rights. I saw potential in Saudi society that intrigued me and gave me some guarded optimism for the future, particularly in the coastal city of Jeddah, where my family had lived those years before and where I ended my journey.

Jeddah is a port city, which means that it has naturally always had greater cosmopolitan influences than the harsh interior of the capital Riyadh. The Saudis there tend to be a mix of different ethnicities, just as many people I met in Medina alluded to ancestors from India, Turkey, or the Levant. The city is home to a beautiful corniche that is currently being expanded to be walkable on temperate nights. The mixture of palm trees, green grass, and gentle waters brings to mind California.

Much of modern Saudi Arabia was built according to 20th century American urban planning styles, which focus on huge roads and highways that privilege automobiles over human beings. Taking America as its tutor, the Saudis emulated every mistake the U.S. made when it came to building their cities. But just as Americans have learnt their lesson from these errors and are correcting course, Saudis seem to be rethinking things as well.

Not far from my father’s old hotel, there is a historic neighborhood called al-Balad boasting narrow streets and colorful wood-windowed buildings. The area had long ago fallen into poverty, but is currently undergoing a renovation aimed at turning it into a tourist destination. The renovation is still in progress. but you can feel the streets already starting to bustle back to life after generations of neglect, with small shops run by Saudis selling carpets, candies, oudh, and traditional dishes. I even saw a few small tourist groups of Europeans and Americans walking through al-Balad with guides explaining to them the local architectural styles, a scene that surely would have been unheard of in Saudi Arabia in years prior.

Being in Jeddah allowed me to compare notes from my father’s account of life there, and there were clearly some major changes. The thuggish religious police, paroled ex-convicts who got the job as a reward for memorizing the Quran in jail, have been banished from sight and no longer force you to prove that the woman you are with in public is your wife. As friends described to me, corruption in daily affairs and business has become far less in recent years, after members of the flamboyantly corrupt old elite had been punished for their antics. Infrastructure seemed to be improving, though there were grumbles that the undemocratic nature of planning decisions had kicked some people out of homes and businesses without consent. I’ve been to enough countries to know that a patina of normalcy can often conceal volcanoes of rage below. But generally speaking, I did not get that impression here.

The most heartening thing that I saw in Jeddah and throughout the country was that Saudis, who were famously absent from their own economy during my father’s time, were really working hard now. Everywhere I went I saw Saudi young people not just engaged in employment, but doing the type of jobs that build character early in life. Restaurants, small stores, taxis, and administrative buildings were notably being run mostly by Saudis themselves. The high-speed trains between cities, housed in beautiful stations built in neo-traditional style, were operated by remarkably young crews, mixed young men and women, who put observable pride into their duties. Expatriate labor is still important in Saudi Arabia. But you can tell it is becoming a real country, rather than a mere confection like Dubai or Bahrain, thanks to the dedicated labor of a new generation.

After spending a few days in Jeddah retracing my fathers steps, I took a train back to Medina to rest under the canopies of the Masjid-e-Nabawi for a few days, before flying back to my home, nestled in the distant towers of New York City.

Vision 570

After recovering from a few days jetlag, I resurfaced from this trip with a renewed desire to spruce up my Arabic, as well as a long reading list of books on Saudi Arabia that I plan to get through in the coming year. I was touched by the hospitality and kindness of many Saudis that I met, and I truly wish the best for their country. I got a sense of what my father meant when he spoke so warmly about his time in this land, which was the last place our family lived before embracing new identities as Westerners. The hazy memories of childhood in my mind have now been replaced with vivid pictures of a country trying to navigate a hard path to modernity.

Saudi Arabia could make very positive contributions to the stability and prosperity of a troubled region, and it has a last shot to do so now with the oil era entering its twilight. No one has had a better past century than the Gulf Arabs, who became fabulously rich, moved back to the center of Islam after a millennium of eclipse by Turks, Persian, and Indians, and who have mostly managed to avoid the carnage and bloodshed of the modern Middle East. If they can stick the landing now and transform their societies into their dream of “Singapore with Islamic characteristics,” even with the imperfection that implies, they will have assured a happy future for their descendants.

I want Saudi Arabia to succeed, and whatever criticisms I have made of its condition I hope are taken in a spirit of camaraderie and sincere counsel. What I would hope to see from its leaders are less investments in science fiction projects promoted to them by sleazy Western consulting firms, who I know are not that competent and also hold Saudis in contempt, and more investment in the country’s patrimony by beautifying their existing cities, where millions of Saudis live and that could still become beacons of refined urban culture. Letting a broad range of voices from society weigh in on their future is an integral part of making sound decisions, and they will need to make many in the years head.

As for Islam, it would be a lie to say that I am not distressed about its material conditions and the decline of much of its civilizational sophistication, so evident at many of its holiest places. The weakness, backwardness, and paralysis of the Islamic world, most recently witnessed in Gaza, is simply a reflection of a religion and people who have fallen into obvious decay. Yet as long as Islam remains a basis for fraternity and love across races and cultures, as well as connection with the divine, it will still hold a place in the hearts of billions around the world who keep returning to sit under the shade of the Masjid-e-Nabawi, myself included.

Beautifully written. I learned so much from this piece!

Making dua for your dad. Umrah mubarak. I appreciate this so much and I wish I had the same experience as you in Madina. It will almost be close to a year since my first Umrah in conscious memory (my first actual umrah was when I was a baby). My experience of Madina was not like yours because during my Umrah, I had my baby with me and I was barred from entering the masjid because of said baby. I believe the restrictions have lifted now. Truly felt that the appalling Nusuk app system, being subject to the ever-changing decisions of a kingdom about Masjid e Nabvi as it is now. Despite the hyperconsumerism in Makkah, I found immense peace just because of the Kabah. Being a woman, I could pray near the Kabah despite not being in ihram. In Madinah, women had to pray with their little ones in the courtyard even with the temperature being 36-40 degrees. When attempting to enter through the gates, the female guards would point to the baby and and say "no baby". With the exception of entering from Gate 32 (Imam Muslim Gate) where some of these guards almost ushered me in when they saw me carrying my less than one year old, none of the other many gates had that generosity. I mentioned the essentially dysfunctional Nusuk app (though some say it's good to have an appointment booked well in advance of your trip), and there were lots of contradictory directions from mosque staff. Random rules and yelling by security. (Some traumatising) crying by pilgrims who spent way too much and travelled from far after a lifetime of being able to save up for a trip where their energy, time, and unawareness of technology is not considered.

What made it Madinah special for me, even in moments of feeling like sheep being fenced in, was trying to imagine what the mosque would look like were the Prophet here. How much more accessible and easier would it be.