Islam Between East and West by Alija Izetbegovic

A Ramadan Reflection

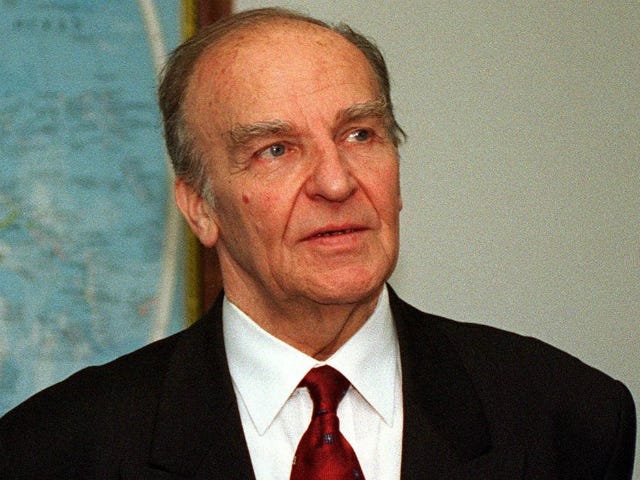

I have never liked politicians and am unlikely to become infatuated with one in the future. There are a few rare exceptions to this rule, however, with one being the former President of Bosnia, Alija Ali Izetbegovic. Izetbegovic was Bosnia’s leader during the horrifying civil war and genocide that accompanied the breakup of the former Yugoslavia. Prior to that he was a well-known dissident intellectual who spent years in prison for his activism. During one of those prison terms, Izetbegovic wrote a book called “Islam Between East and West,” that remains one of my favorites to this day.

Given that its Ramadan, which has been one of the most rewarding and challenging aspects of my life in all the years that I’ve observed it, I thought it would be interesting to explain some of the underlying philosophy behind the tradition through the lens of this fascinating gentleman and his writings. Izetbegovic came of age under Communism, in a world that had seemingly left religion in general behind it. The book he wrote sought to explain what he saw as the merits of Islam to a thoroughly secularized and skeptical European society, which he felt had suffered an unacknowledged spiritual wound as a result of its secularization.

As Izetbegovic writes, people have both material and spiritual needs. To nourish one at the expense of the other is to live in a manner that will produce disharmony. Christianity is very metaphysically focused, a “pure religion.” Ideologies like Marxism meanwhile counsel an equally strident “pure materialism.” Yet for human beings to be at peace with their existence and to flourish, they need to partake in both the inner and the outer life. Islam is intended as a means of living the “middle path” between these two poles. The philosophy of Islam, which medieval Christian polemicists criticized as carnal, and modern materialists as otherworldly, is intended to make people to live in balance – encouraging them to partake in the permitted good things of the world, while also holding onto a metaphysical perspective on their existence. This philosophy of religion is embodied in the act of Islamic prayer, which combines both physical and meditative activity into one practice. The goal is to enchant the world, rather than experiencing it as the workings of one big dead machine, while also keeping in mind that we are travelers and this is not our final destination.

Izetbegovic was deeply familiar with the popular ideologies of modern secular Europe where he was raised. In his book, he conducts a comparative analysis of modern materialist ideologies with Islamic thought. I will not retread all his arguments here, but of great interest to me was his sympathetic take on nihilism and nihilist literature. Nihilism is a school of thought often viewed as anti-humanistic to the point where to describe someone as a “nihilist” today is essentially a substitute for calling them evil. Izetbegovic had a very different take, and saw nihilism as a pained longing for metaphysics in a culture that has denied it – an essentially religious yearning. As he writes, “nihilism is the religion of those disappointed in not finding the divine.” Both nihilism and religion effectively recognize the existence of a soul and an essential human foreignness to the world. The difference is religion claims to have found a way out, while nihilism does not.

For millennia, belief in the Divine gave people a sense of grounding and self-assurance with regard to their own existence. There was a world that they lived in, for better or worse, but also another world that they felt, but could not see, yet which was equally as real. The “Death of God,” later proclaimed, or at least recognized, by Nietzsche, meant that this connection had closed off for people with a secular nomos. With God gradually fading out of the picture, earthly existence suddenly started feeling to many people like a prison. Rather than warm and welcoming, even when it was hard, life itself began feeling alien, frightening, and somehow unnatural even when it was comfortable.

This unsettled feeling itself produced nihilism, which, rather than being anti-human, is a posture of woundedness in the absence of metaphysics. Secular metaphysics suggest that man is simply a higher breed of animal. Yet this existential crisis, which often produces suicide or other acts of self-destruction, does not evince itself in any animal. It is purely a human phenomenon. Nihilism proclaims man fundamentally alien to this world, and then despairs that there is no way out. Islam with its “middle path,” agrees that we are to some extent foreigners here, but describes the path as a journey and tries to identify a safe path to make it through.

If you are familiar with Platonic thought, you will see echoes of his worldview in that of Islam. In the Islamic conception of the world, as Izetbegovic writes, mankind is unique among creation for serving as the vice-regent of the divine within the material world. All created things are by nature obedient to the divine will, and thus live in the manner that they have been designed. It is only humans who have the ability to choose whether to rebel or submit themselves to the natural order. Through their possession both an inner and outer life, humans potentially serve as the vehicle through which the divine attributes are projected into the material world, providing what we could describe as a moral influence upon a creation that would otherwise be deterministic and mechanical. For a human to live in accordance with their prescribed divine nature, as a flower or a bird does naturally, while we must strain and fight to achieve it, is to be considered “Muslim.”

That all brings me back to Ramadan. In the off-chance one doesn’t know, Ramadan entails abstaining from food and water during daylight hours, while making other minor adjustments in your life oriented towards being more God-conscious, or “spiritual.” I wouldn’t say that its a tradition that is easy or fun in the manner of Christmas. In fact, it can be quite taxing. But given that so much of life is mindlessly oriented towards corporeal pleasure and satisfaction there is something liberating about living in the opposite manner, even for one month of the year. There are two philosophical benefits as well. On one hand, it puts you more in touch with the experience of the poor, who suffer thirst and hunger to a level most of us are unfamiliar with today. But more profoundly it refutes the materialist conception of human beings as merely animals, or machines for living. Acting against your biological imperatives is a proof that you are not merely your biology, and are something greater than that. When you experience it in the midst of your fast, it is a very clarifying reminder.

I will close with some words about Ramadan by Izetbegovic who was both a great Muslim and a great European. I took the photo below at his grave in Sarajevo a few years back. “Fasting is an exclusively human choice,” he wrote. “Both, man and animal feed themselves. Only man is capable of fasting. Fasting is the highest expression of will, it is an act of freedom.”

Beautiful summary. Thank you. I will share with my 17 and 15 year old boys who insist on fasting every year without me requiring or requesting it. It speaks to the spiritual yearning that you mention.

I read all his works in Arabic (due to the great interest in the Bosnian war in the Arab World). All his works were translated from Bosnian by an Egyptian professor, and I have to say this book is probably the 2nd most influential book in my life and has the biggest impact in shaping my worldview. It also opened my eyes into an Islamic worldview that is significantly different than the traditional theological worldview. It's very hard to provide an "Islamic Political Theory" without referring to Izetbegovic for modern Islamic political theory. I still want to read it in English though. What I got to know is that The Bosnian book was called "Between East and West" and the translators added "Islam" to the title.