A New Guide to Passive Language Learning

Language learning in an age of rapid technological change

A few years ago, I wrote an article titled “How to Teach Yourself a New Language.” The article grew out of a personal interest in linguistics, and my own experience passively studying Persian and Turkish. Over a few years, I succeeded in taking these languages from nearly scratch to a high-intermediate level of proficiency, without attending formal courses or interrupting my personal and professional life.

My aim in that article was to share my methodology for successful part-time language self-study, based on slow-and-steady repetition and digital immersion. I hoped it would help others with a similar interest, but also encourage people to learn a new language as a way of reclaiming something human in the face of degrading technological hyper-stimulation.

Since then, I have applied the same methodology to Levantine and Modern Standard Arabic. While I cannot claim the same level of fluency with such a challenging and capacious language, I have made great progress and developed further confidence in my approach. Currently, I am developing my ability to read and speak Mandarin, a language with which I had no prior familiarity.

In general, I believe I have become quite adept at language learning and have something to teach others. For me, its essentially a hobby, but it is one that has provided tremendous personal and professional benefits. In addition to knowing Urdu through my family background, I have latent familiarity with French and Somali, which I could scale up if I wished. In theory, I could speak seven or eight languages.

If that seems intimidating, it should not. There are many people around the world who are polyglots, including people I have met in countries with minimal resources who have amazed me by speaking many different languages with near-native fluency. There is a lot of propaganda—sometimes promoted by expensive, for-profit educational institutions—about how difficult, time-consuming, and expensive language learning must be.

I once believed this myself, and it dissuaded me. In contrast, I argue that learning a language is not inherently hard. Modern technology has in fact made it easier than ever, even for those with limited time and resources.

Part of the trick is taking some of the negative psychological externalities of the digital age—shortened attention spans, information overload, AI slop—and redirecting them towards something positive and constructive. With that in mind, I wanted to write an updated version of “How to Teach Yourself a New Language”, including refinements I’ve developed over the past two years.

I am presently applying this method to Mandarin, which I study passively for enjoyment, currently reading and speaking at HSK Level 2. Rather than devoting a huge amount of time, I incorporate Mandarin study into my daily life—working, having a family, exercising, and reading books. The main modification is exposing myself to more Mandarin-language news sources, which also complements my research interests.

Learning a language is mostly about patience, motivation, and developing habits. To achieve proficiency, you need a certain number of exposure hours, which vary by language complexity. For a simpler language like Spanish, about 600 hours may suffice. For complex languages like Mandarin or Arabic, closer to 2,000 hours may be needed. But as long as you persist, you can reach an intermediate level or higher without expensive courses, moving abroad, or even devoting a lot of your day to it.

Timed Repetition: Flashcards, DuoLingo, Clozemaster

For years, I’ve hosted a podcast on contemporary geopolitics and armed conflict. At the start of each episode, I read a script aloud two or three times before recording. After a while, I noticed the neurological effect of repeated readings: your mind begins to settle into a groove, developing familiarity and eventual fluency with previously awkward material.

Learning a language operates along the same principles. To learn a word or a sentence, you have to see it and say it a few times, after which your mind will start to get comfortable. In my experience, to learn a particular foreign word you need to encounter it on an average of six to eight nonconsecutive occasions. Ideally, you should encounter it in a different context each time.

If you live abroad or attend a course, repeated encounters are built-in. But if not, you can create them yourself using a few tools. This is where the digital world that many of us interact with can actually come in handy, rather melting our brains and dulling our intellect.

Every day, once a day, I review a set of flashcards containing words and sentences from the Mandarin language. I do this using a free program called Anki, which I also used to study Persian, Turkish, and Arabic.

During a period of downtime in my day, usually right when I wake up, just before bed, or while I’m taking the subway, I will read five sets of Anki cards containing 50 cards each. Importantly, these are all cards that I wrote myself of Mandarin words and sentences that I want to learn, rather than a preexisting set that someone else made. During the day, I will spontaneously add new words and sentences that I encounter.

When possible, I speak each word out quietly in order to improve my pronunciation. Speaking the word out loud also helps develop the neural connections that are vital for memorization. The benefit of Anki as opposed to traditional flashcards is that it also automatically detects the cards that are your weakest, and structures each daily set in a manner aimed at improving those.

Each day you do a certain set of cards, it becomes relatively easier. After a few weeks, you find yourself breezing through sets of words and sentences that you now know by heart.

On a typical day I may cumulatively spend 30-35 minutes reviewing these cards, which also include some review cards from Arabic, Persian and Turkish to prevent atrophy in those languages. That may seem like a long time at first glance, but it pales in comparison to the average time that many of us otherwise waste looking at TikTok, Instagram, or zoning out to the many other forms of psychic death delivered via our cellphones.

In addition to this daily flashcard routine, there are two gamified language learning applications that I use on a regular basis, and which I try to do at least one or two levels on before going to sleep at night. The first is Duolingo, which, contrary to the views of some language snobs, is actually a very effective means of structured repetitive learning, especially when you are developing early familiarity with a language.

The other application I use is for people studying more advanced vocabulary, and is called Clozemaster. Clozemaster gives you fill-in-the-blank sentences in a range of languages and consists of a similar (albeit less slick) gamified user experience as Duolingo.

Using each of these applications for 10 minutes a day will be more than enough to make slow and steady progress in any language, while giving you the structured, repetitive encounters with words and sentences that are the building blocks of fluency.

Its estimated that the average person now spends four to six hours on their phones a day doing non-essential tasks, or “killing time.” Many people spend far more than that. At most, you will spend an hour a day at this type of language review, and will eventually have a great reward to show for it. How much time have you spent fruitlessly scrolling through your Instagram feed this week?

Structured Immersion: Music, Videos, Conversations

In addition to this conscious time spent language learning, I do several other things that allow me to passively immerse myself in Mandarin.

Although I’m not extremely abstemious, one thing I do generally abstain from is watching television (I also do not drink alcohol). But if I do want to unwind and watch something, I make sure to watch Mandarin-language television shows and films that give me additional exposure to the language.

Likewise, when running and going to the gym, I listen to contemporary music from China. You may not know this, but, like many Asian countries today, China has a great rap music scene. Because of its emphasis on meter and rhyme, this genre is excellent for language learning and memorization. Where possible, I will try to find and read the text of the lyrics to songs that I like, so that I can internalize them naturally over time. (Memorizing poetry is also great for literary languages like Persian and Urdu.)

On social media, I follow Mandarin language accounts. This has gradually changed my algorithm to give me more such content, including both video and text. When I see or hear words that I have not encountered before on a social media stream, I will translate them, and then enter them onto an Anki card for later review.

Likewise, inasmuch as I use TikTok, a lot of my content is now Mandarin-based with subtitles. As a result, instead of just being mindlessly entertained by short-form video, I learn something useful from even trivial forms of content.

Though I am not yet ready to do this with Mandarin, once I reach a certain level of proficiency I will change my devices to that language. This forces you such to encounter certain words constantly when doing daily tasks like setting a schedule, or navigating with Google Maps. For a number of years now my phone language has been in Turkish. Gradually, my familiarity with a large number of Turkish terms improved. At this point, its like second nature.

On top of all that, I always find opportunities to speak with friends and acquaintances in the languages that I know. I do not have a huge ego, nor am I particularly embarrassed to make mistakes (pro-tip: humility is very important to learning anything) so I’m glad to strike up conversations with people in Mandarin, even if its a few phrases, or to reach out to my handful of Chinese friends to have short discussions in Chinese and get their feedback.

I do the same thing with the other languages that I know well, and have had great experiences both at home and abroad. Those interpersonal connections and conversations are by far the most rewarding aspects of learning a foreign language.

Structure: Coaching and AI Assistance

For all that I have said about passive learning, it is necessary to have some degree of structure in order to truly learn a language. Language learning is a skill that is transmitted in a way comparable to an apprenticeship. To make verifiable progress, you need attention from someone who has mastered the craft, and is willing to provide you a degree guidance along the way.

To this end, as I have done with every other language I’ve studied, I have an online Mandarin tutor with whom I do periodic lessons. I do this on weekends in the early morning while everyone else is asleep, using an inexpensive online tutoring service called iTalki. A tutor is helpful in filling in the gaps of a language, including grammar, syntax, and conversational practice. But they also give you the important asset of an outside party who is able to gauge and direct your progress over time.

Many people are skeptical or critical of AI, and I share some of that skepticism. But given the degradation of traditional search tools like Google Search, it does help in looking up sources of information. I’ve also recently found it useful as a tool for rapidly accelerating progress with language learning.

An LLM is a platform that you can subject to constant interrogation about various subjects. While you should definitely not ask it to give you a concrete “truth” about any abstract topic, nor should you fall in love with it or make it your therapist, it can be useful for technical tasks like writing code. It is also very good at explaining the structure of a foreign language.

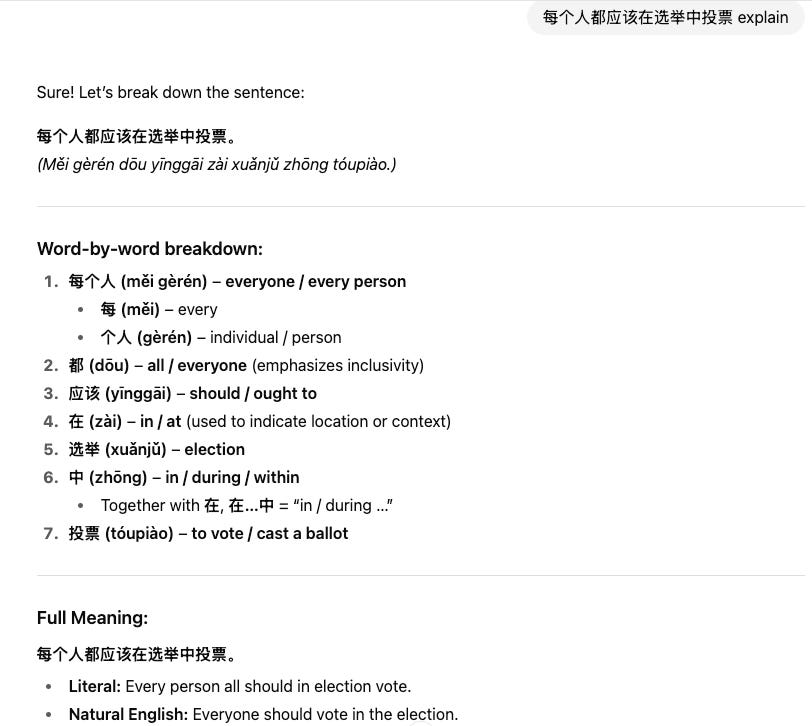

I frequently ask ChatGPT and other LLM programs to explain particular Mandarin words and sentences that I come across, and to give me granular breakdowns of particular ones that I find challenging. I also ask it to make sentences for me out of words that I want to know, so that I have additional examples that I can later use for my flashcard decks.

These types of breakdowns are invaluable. If one were learning in the context of a college education, you’d normally have to book office hours with a professor or hire a specialized tutor to get specialized attention like the conversation cited in the image above. But with an LLM you can simply query it at any moment of curiosity.

LLMs tend to hallucinate and transmit false information far less when it comes to language learning, which is a relatively static field subject to less contestation. Being able to ask it questions, receive breakdowns, or even create small hyper-specialized exercises and lessons is an incredible benefit. It allows you to skip the experience of being “stuck” on a particular subject, which is frustratingly common when receiving a traditional education.

While AI can be a bad thing when used uncritically that destroys human reasoning and cognition, when used with discernment it can instead be a powerful tool that actually sharpens your mind instead of degrading it.

Motivation, Intention and Patience

These tools can all help you learn a language. But they will not succeed without your own patience and motivation. To learn a language passively, you need to be comfortable with the idea of delayed gratification. You also need to truly want to learn in a way that is more than just a fleeting desire.

Learning a language is like taking a long car journey. You need to know where you are going and be committed to getting there, such that you will not be deterred by any inevitable roadblocks or traffic jams that spring up along the way.

If you asked me why I learnt Persian, Turkish, and Arabic, its because I either spent time in places that these languages are spoken, wanted to be able to access some rarefied cultural or religious knowledge, or sought to make personal and professional connections with native speakers.

I’m learning Mandarin now because I think it will be a very important language in the future due to shifting political and technological trends, and I’d like the ability to comfortably access information related to China in the same way that I often can with the Middle East.

This will take some time. I estimate I will need around 18 to 24 months of habitual passive exposure to reach my targeted level of HSK4 proficiency. In that time, I also have a lot of other personal and professional milestones that I plan to achieve. My expectation is that I am going to make it, simply as a result of adopting the practices that I’ve laid out in this article.

I have not introduced any major disruption into my life. I simply try to cut out excess, and incorporate a few language learning habits in my routine. Barring some unforeseen calamity, I look forward to comfortably speaking and reading Mandarin at an intermediate level in the next year or two. I am confident you can do the same, with whichever language you are currently coveting.

Some may retort to this article by saying that I’m really smart and this is not typical, or that they simply do not have the time. My response would be that these tools work for anyone, there are plenty of things I don’t know, and that if your verbal IQ is lower the only difference is that you may need to see the same word ten times instead of six in order to learn it. I also do not have time, and am actually overwhelmed with personal and professional responsibilities. But I make a point of carving out a small portion of my time for this because it motivates me and is something that I enjoy.

People like Elon Musk contend that learning a language has become an antiquated skill as a result of advancements in translation technology. I strongly believe the opposite. Language is a critical part of what makes us human.

Even if I could use Google Translate to communicate with someone in rural Anatolia or the old city of Damascus, I will never make the personal and emotional connection that I can by conversing with them in their native language. You simply do not get the same satisfaction from life by offloading even more human interaction to technology.

The benefits of the foreign languages I’ve learnt have been unexpected and beyond calculation. I’m certain it will be the same with any new ones I may choose to learn in future.

If you’re debating whether to start learning the language that you have been coveting, please take this as a signal to do so. If you ever need advice or want to discuss, you are welcome to reach out to me to commiserate. I’m glad to share new tips that I come across on my own endeavours.

The Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini once said, “A different language is a different vision of life.”

May we all continue to have many more visions of our shared life.

This is beautifully written. I would think of it more as ‘slow learning’ than ‘passive learning’. It doesn’t seem all that passive!

Very inspiring! I guess I've always been skeptical about the benefits of rote learning like Anki because it relies on repetition and more lower order learning. But this is language learning we're talking about, so repetition IS one of the keys! I think you've convinced me to give flashcards a shot. Thank you for your valuable tips!